When Your Child Has an Atrial Septal Defect (ASD)

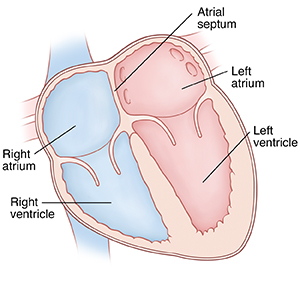

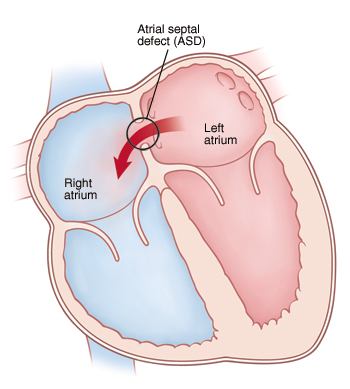

The heart has 4 chambers. An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a hole in the dividing wall (atrial septum) between the 2 upper chambers (atria) of the heart. There are 4 types of atrial septal defects:

-

Sinus venosus defect. This occurs in the superior or inferior parts of the atrial septum.

-

Secundum defect. This occurs in the middle part of the atrial septum.

-

Primum defect. This occurs in the part of the atrial septum, next to the heart valves.

-

Coronary sinus defect. This occurs when part or the entire common wall between the coronary sinus (which normally drains into the right atrium) and left atrium is absent.

An ASD can lead to certain heart and lung problems over time. But it can often be treated.

|

| An ASD lets more blood than normal circulate through the right side of the heart and the lungs. |

What causes an atrial septal defect?

An ASD is a congenital heart defect. This means it’s a problem with the heart’s structure that your child was born with. It can be the only defect. Or it can be part of a more complex set of defects. The exact cause is unknown. But most cases seem to occur by chance. Having a family history of heart defects can be a risk factor.

Why is an atrial septal defect a problem?

Blood normally flows from chamber to chamber in one direction through the left and right sides of the heart. With an ASD, blood typically flows through the defect from the left atrium to the right atrium. This is called a left-to-right shunt. It causes more blood than normal to pass through the right side of the heart. As a result, extra blood has to be pumped by the right side of the heart to the lungs. This leads to the pulmonary arteries and right atrium getting larger. Over time, too much blood flow to the lungs increases the pressure in the pulmonary arteries. These are the blood vessels leading from the heart to the lungs. Left untreated, the pulmonary arteries can become damaged. Irreversible lung problems can then occur in adulthood. And children who are not treated are at increased risk for heart arrhythmias, such as atrial flutter or fibrillation.

What are the symptoms of an atrial septal defect?

Most children with an ASD have no symptoms. ASD is often discovered if your child's healthcare provider hears a murmur. Or your child has an echocardiogram for some reason. Sometimes the large atrial size may be seen on a chest X-ray. If a child has symptoms, they can include:

-

Tiring easily during exercise

-

Difficult and rapid breathing

-

Frequent lung infections

-

Slow growth

-

Migraine headaches in older children

-

Stroke from blood clot

-

Abnormal heartbeats (arrhythmias) increasing over time

How is an atrial septal defect diagnosed?

During a physical exam, the healthcare provider checks your child for signs of a heart problem, such as a heart murmur. This is an extra noise caused when blood doesn’t flow smoothly through the heart. If your child's healthcare provider suspects a heart problem, your child will be referred to a pediatric cardiologist. This is a healthcare provider who diagnoses and treats heart problems in children. To check for an ASD, these tests may be done:

-

Chest X-ray. X-rays are used to take a picture of the heart and lungs.

-

Electrocardiogram (ECG). The electrical activity of the heart is recorded.

-

Echocardiogram (echo). Sound waves (ultrasound) are used to create a picture of the heart and look for structural defects.

How is an atrial septal defect treated?

Some ASDs, such as smaller secundum defects, may close on their own in the first few years of life. So the cardiologist may check your child’s heart regularly and wait to see if an ASD closes or gets smaller.

If an ASD is moderate or large or doesn’t close on its own by the time your child is school age, your child's cardiologist may advise closure. This can be done with either cardiac catheterization or open-heart surgery. The cardiologist will assess your child’s condition and talk with you about treatment options.

What are the long-term concerns?

-

An ASD that’s left untreated can lead to other health problems later in life. These can include high blood pressure in the lungs, lung disease, and a higher risk of stroke as an adult.

-

After treatment, most children with an ASD can be as active as other children. Talk with your cardiologist about any activity restrictions.

-

Your child will need regular follow-up visits with a cardiologist. Your child will need less of these visits as they grow older.

-

Your child may need to take antibiotics before having any surgery or dental work for 6 months after the ASD repair. This is to prevent infection of the inside lining of the heart and valves. This infection is called infective endocarditis. Ask your child's cardiologist about this.

Online Medical Reviewer:

Amy Finke RN BSN

Online Medical Reviewer:

Scott Aydin MD

Online Medical Reviewer:

Stacey Wojcik MBA BSN RN

Date Last Reviewed:

9/1/2022

© 2000-2024 The StayWell Company, LLC. All rights reserved. This information is not intended as a substitute for professional medical care. Always follow your healthcare professional's instructions.